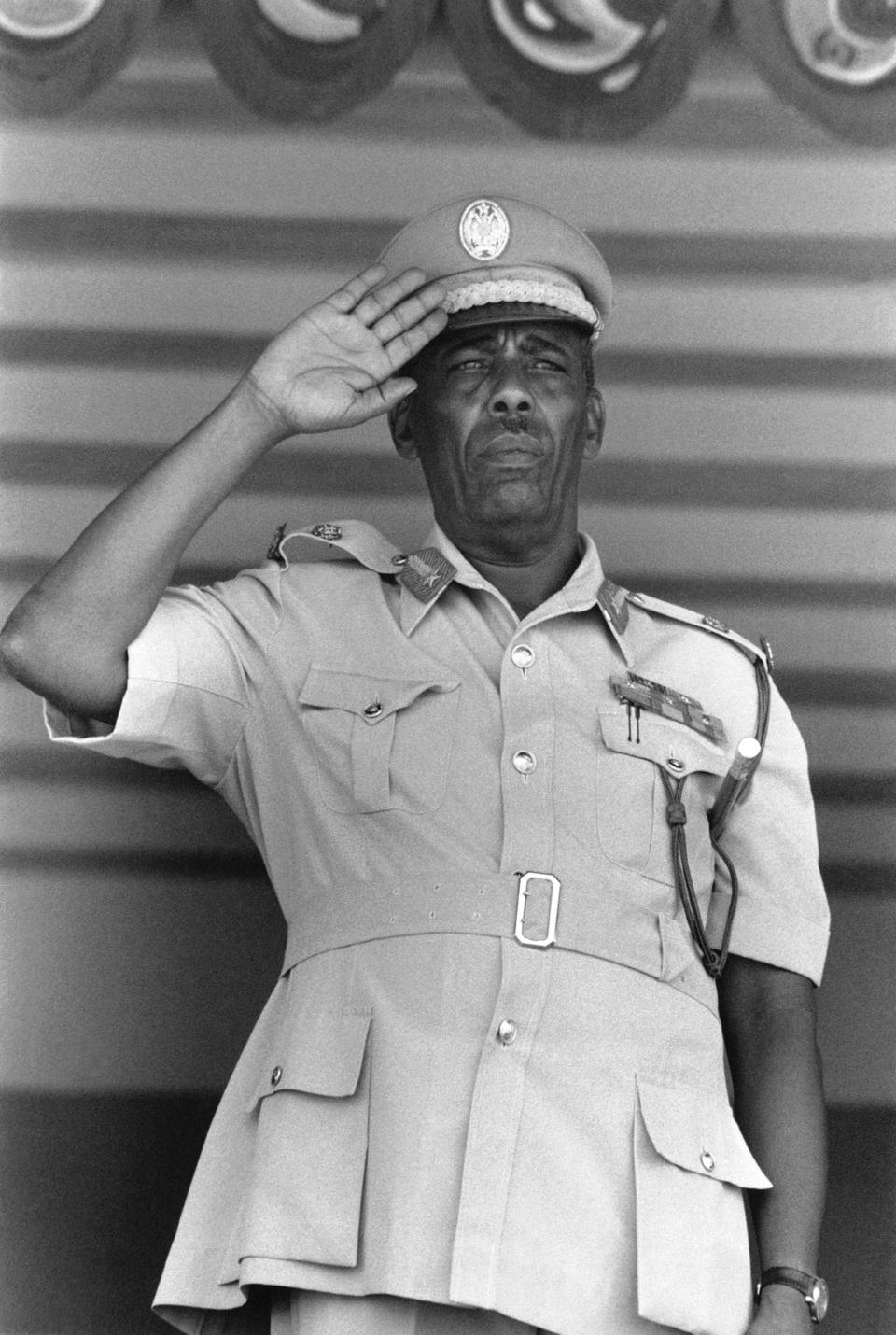

Fifty years ago today in Somalia, Mohammed Siad Barre’s military coup ended Somalia’s brief democratic period, which paved the way for civil war when the regime eventually collapsed. His contested legacy divides Somalis to this day.

On the morning of October 21 1969, in the young Somali Republic, Radio Mogadishu had been playing unusual militaristic music most of the morning, deviating from its usual programming, which began with a round-up of world news.

Just a week earlier the incumbent President Abdirashid Ali Shermarke, had been assassinated in what some historians believe was an act encouraged by the Soviet Union. And just the day before Prime Minister Muhammad Egal was distributing money which he’d plundered from the Somali Central Bank among corrupt politicians. He would find himself placed under house arrest the next day, on October 21, by a group of rogue soldiers, whilst his accomplices were driven past rapturous crowds to a presidential retreat in Afgoi where they would be detained with other MPs.

The government was informed that it had been dissolved by the military. “You are nothing,” one of the guards told them.

The public enthusiastically welcomed the coup d’état, and only several days later would it become known that Siad Barre, commander of the Somali armed forces, masterminded the operation which ended Somalia’s short-lived and hopeful but troubled democratic era.

Adan Shire Lo, an MP who was arrested, was the brother-in-law of Barre’s wife. Upon learning about the coup, Adan’s wife visited former president Aden Abdulle Osman, who lost the 1967 election, and told him “this is the beginning of the end of Somalia”. Her words were prophetic.

This was one of the defining moments in Somalia’s post-independence history, with Siad Barre – arguably the country’s most influential leader – using authoritarian methods to develop the country, before a series of challenges exacerbated by his heavy-handed approach to governance turned Somalia into what contemporary observers often say is a “failed state” after his regime fell.

His shadow still hangs over Somali politics to this day, dividing the victims of his crimes from those who look back nostalgically at their lives in a much more peaceful Somalia.

Barre’s Socialist era

Born in the early 20th Century in Italian Somaliland, Siad Barre was in many ways a product of the colonialism he later rebelled against. He joined the Italian Carabinieri and even served in a campaign for Italy against Ethiopia. When Somalia fell under British Military Administration, he continued his rise to the highest office a Somali could hold as police inspector. When Somalia became independent and the Police Force of Somalia turned into the new republic’s army, he eventually rose to the top of the Somali armed forces, following the death of former commander General Daud Abdulle Hersi in Moscow, before overthrowing the government in 1969.

On October 24, in his first speech after the coup, Siad Barre would set a new tone for the country.

“Intervention by the armed forces was inevitable,” he said. “I would like to ask all Somalis to come out and build their nation, a strong nation, to use all their efforts, energy, wealth and brains in developing their country,” he continued.

“The imperialists, who always want to see people in hunger, disease and ignorance, will oppose us in order that we may beg them… let us join hands in crushing the enemy of our land.”

By November 1, he would suspend the constitution, dissolve parliament, ban political parties and abolish the Supreme Court. Without a hint of irony, the country was later renamed the Somali Democratic Republic, and the conspirators founded the Supreme Revolutionary Council.

Mohammed Abdulrahman, who would later work in the Ministry of Livestock, was a secondary school student when the coup happened and recalls the event vividly. “We were all jubilant,” he said. “Students went outside running in the streets, we were throwing our books. I remember that day, it was a really special day, and we had huge hopes of what was to come, and in the coming eight years a lot was achieved.”

He added: “That was the turning point for Somalis, people were fed up of the old corrupt and tribalistic government which claimed to represent us. At the time, the government was so bad that we didn’t think about the consequences.”

Barre immediately began mobilising Somali society with the Jupiterian powers he had concentrated in the government’s executive branch, with the hope of building a socialist society. Hantiwadaag, literally ‘sharing of wealth’ in Somali, or socialism, was to soon be the new ideology. Somalis were also ordered to call each other ‘jalle’, the Somali equivalent for comrade. Barre would take the title Guulwade, or Victorious Leader, as he began working to create a cult of personality.

When asked about the compatibility of Islam – the faith majority of Somalis adhere to – and socialism, Barre responded: “No chapter, not even a single word, in our Koran opposes scientific socialism. We say, ‘Where is the contradiction? The contradiction was created by man only.”

“There has to be a distinction made between the first few years and from 1976 onwards” Professor Abdi Ismail Samatar, author of Africa’s First Democrats tells TRT World. “The way they dealt with the droughts, that prevented a wide scale famine for example. The introduction of a written Somali language is still used today in Djibouti, Ethiopia and Somalia, the award-winning literacy campaigns, healthcare improvements, universal education and better infrastructure. Those were the highlights, but there was always a creeping authoritarian trend in his rule.”

Modern Somali culture also really took off, says Professor Samatar, often with a strong anti-colonial and pan-African character with music hits like There’s a Bone in this Date and Together Reject Colonialism.

“They really mobilised the population with music, theatre, public relations and other things,” says Abdulrahman. “And we were proud of the role we played in supporting other African liberation movements in Zimbabwe, South Africa and elsewhere.”

This was consistent with the foreign policy of the Somali government in Africa, supporting, both materially and morally, independence movements across the continent, a policy largely shared with the Soviet Union, with which Somalia signed a treaty of friendship in July 1974.

“They saw us as ‘messengers of heaven’,” wrote Georgiy Ivanchenko, a Soviet author who visited the country.

“Around that time I was expecting to come to the UK, on scholarship, but that changed because Somalia began drifting away from the West,” says Mohammed Abdulrahman. “At the time Somalis loved Russia, we had a problem with the West because of the experience of colonisation, and what they were doing to other Africans.”

“Those years, until the Ethiopia war,”he says. “Were the best years, the golden era of Somalia.”

“When we lived in Mogadishu life was so different,” he recalls, showing me photos of the city in the 70s. “Every day was like a weekend in Somalia. We worked until midday and slept until the Asr, this was our siesta, and when we woke up we’d spend the evenings on the beach. We’d sit at Jazira and Lido play football, swim in the sea and drink tea until Maghrib.”

The Ogaden War, the beginning of the end

The Soviet Union had heavily invested in the Somali National Army (SNA), building one of the most formidable militaries in Sub-Saharan Africa. By 1977, with Ethiopia in turmoil, and the balance of power decisively in Somalia’s favour, Barre launched a ground invasion of Ethiopia to wrestle the Ogaden, or Western Somalia as Somalis referred to it, from Ethiopian control. The invasion failed, dealing a serious blow both materially and politically to the military regime.

“That defeat in many ways de-legitimised the Barre regime’s right to govern,” says Professor Samatar. “I think it was a turning point in the sense that it exposed the bankruptcy of the regime in terms of public governance and management of the country.”

He adds: “By the early 80s you could see that the tension was thick in the air.“People weren’t so happy, and the regime was heavily in debt. Internal squabbles came out into the open, factionalism became rife and Barre’s government started to deteriorate and the creeping authoritarianism turned openly brutal.”

Without a committed superpower patron – as Barre’s enduring irredentist foreign policy failed to win him sufficient Western support – and an accident in 1986 which hospitalised him, the Barre regime resorted to violence to maintain its rule.

“The car accident happened near my old home,” Abdulrahman tells

“And the road often became very slippery when it rains, so his car flipped and hurt him badly. When he returned he didn’t have full control anymore, but he and his officers started treating people very badly.”

Despite his condition, he was nominated by his party for the presidency – the country’s sole legal political entity – and won an uncontested election which gave him seven more unstable years.

This was exacerbated by Ethiopian support for rebel groups across the country which led Barre to hire mercenaries to bombard major cities like Hargeisa and Burao, causing thousands of civilian casualties. Eventually, clan-based rebel groups overcame his regime after he flip-flopped on promised elections.

The capital Mogadishu fell into the hands of warlords with much of the south descending into anarchy, whilst the Somali National Movement consolidated its gains over time and eventually seceded, declaring the rebirth of the Republic of Somaliland.

The legacy of his period remains contested among Somalis, many of whom remain caught between nostalgia in a country which has been without a central government for almost as long as it has had one, and those who were victims of the Barre regime’s crimes.

Another person who spoke on the condition of anonymity, whose father was part of the Somali Youth League that was overthrown by Barre, said: “We didn’t have a lot those days and the crimes were unforgivable. Some of my family members died, but much like me, people often say we had a country which though troubled was ours. The regime needed to end, but we all hoped things would go differently after 1991.”

Another person I spoke to said: “The problem with dictators is that they destroy everything they build.” He recalled being imprisoned as a child during a protest against Barre’s repressive policies against religious people who dissented against some of his social reforms, which sidelined religious views of inheritance and dress.

“Some say overthrowing him the way we did was a price worth paying. I have sympathy with that view, but there are still a lot of people who look around almost three decades on and aren’t convinced. It has become hard to make the case that things are better now.”

Source TRTworld